Screens are filling a void left by failed community design

Jonathan Haidt’s The Anxious Generation has sparked an important conversation. Screens and smartphones are undeniably shaping childhood and adolescence in profound ways. But are they the root of the problem, or simply the most visible symptom? Blaming screens is tempting. They are tangible, measurable, and removable. If phones are the problem, the solution feels straightforward: take them away. Yet that framing risks oversimplifying a far more complex reality. One that quietly surrounds us every day.

Anxiety and depression are rising. Loneliness is widespread. Third places are disappearing. Nearly 29% of American households are now single-occupancy, and many people go days without meaningful, face-to-face interaction. These are not just cultural shifts, they are formative social ones.

So how did we get here?

Look at the American landscape. Strip malls over here. Housing over there. Wide highways in between. Neighborhoods separated from schools, shops, and friends by long drives and busy roads. If you have sidewalks, consider yourself lucky. This wasn’t accidental. During much of America’s postwar development, car companies and related industries successfully lobbied for a built environment that prioritized driving over walking, convenience over connection.

The result is a generation that isn’t just anxious, it’s separated.

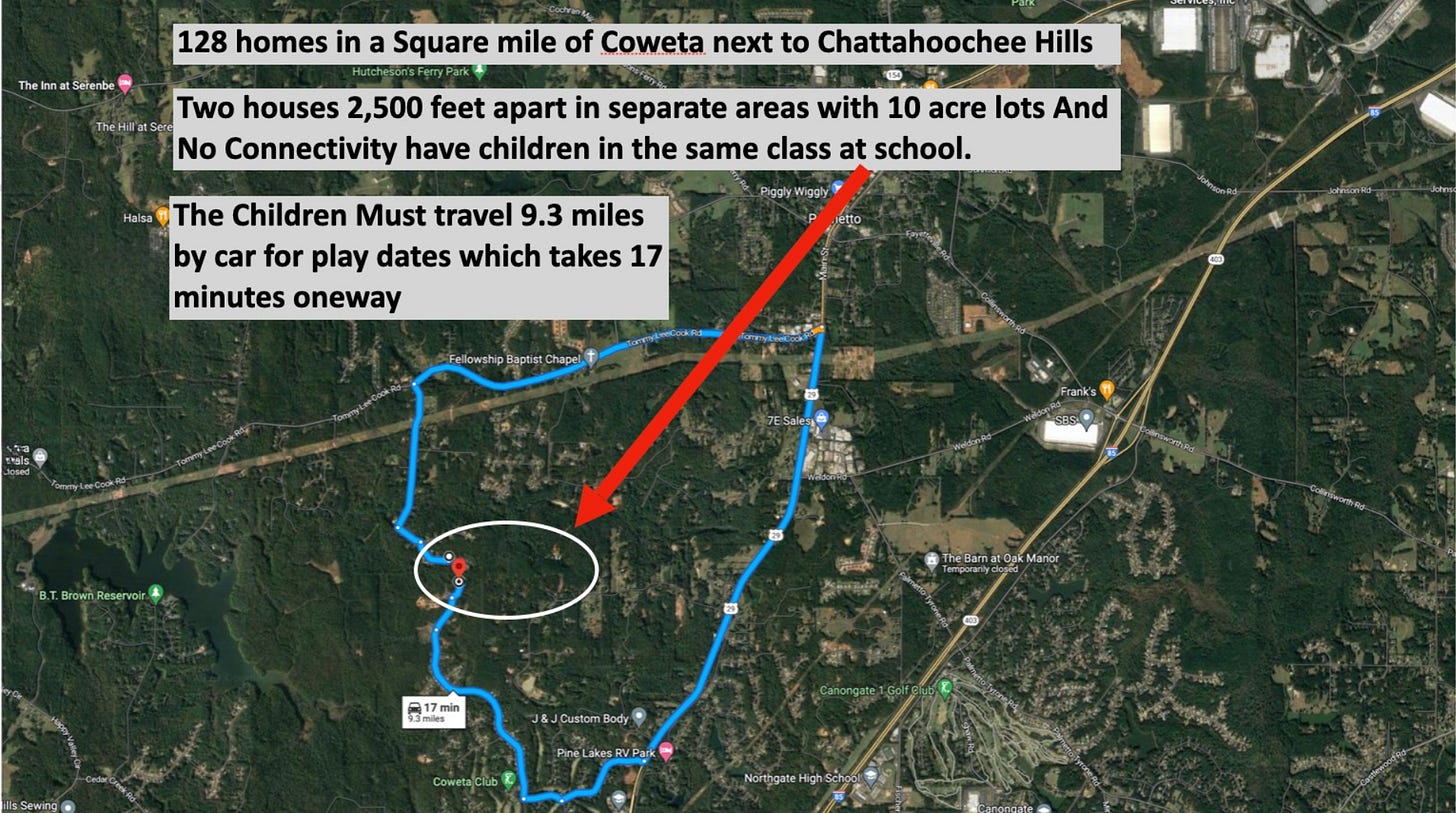

Real world examples can be found in many suburban neighborhoods with one striking local example below. These two homes are only 2,500 feet apart – but a 17-minute, one-way drive creates vast separation that a parent or caretaker must navigate for every single playdate. If sidewalks or a nature trail connected neighborhoods, the kids could safely visit each other within minutes.

Yes, phones are an issue for developing brains. But if kids live a 20-minute drive from their best friend (who should be a two-minute walk away if the built environment hadn’t failed them) then doesn’t the phone at least offer some connection instead of total isolation?

Here at Serenbe, many parents are having meaningful conversations about screens – and that’s vitally important. But we also need to acknowledge a bigger conversation about our built environment and how it has quietly pushed us towards isolation. When children and young adults must rely on a car to see a friend, when homes are fenced off and neighborhoods lack shared spaces, connection becomes effortful instead of natural. Humans are social by design. We thrive on proximity, spontaneity, and shared experiences. This is why solitary confinement is so psychologically damaging. Isolation isn’t neutral, it’s harmful.

Density, when done well, fosters community. It creates chance encounters. It supports independence, especially for children. It allows relationships to form without planning, permission, or a 20-minute drive. At Serenbe, this understanding shapes everything. We fought for mixed-use zoning so homes could sit alongside cafés, trails, farms, schools, and gathering spaces. We believe that walkability is about connection as much as convenience.

Perhaps what we’re facing isn’t simply an anxious generation. Perhaps it’s a separated generation, raised in landscapes that make human connection much harder and less natural than it needs to be.

And perhaps the most radical thing we can do for mental health isn’t simply putting down our phones, but rebuilding the places we live so that connection is once again part of everyday life.